Sleep Webinar Part 2: Understanding Sleep is Key: Professor Cathy Hill

An introduction to sleep: what it involves, and what is needed for healthy sleep patterns.

Note: This series of blogs are drawn from an online seminar that was held on June 30th 2021. It featured the excellent research of Professor Cathy Hill, Dr Rina Cianfaglione, and Dr Lizzie Hill. The live seminar was very well attended, demonstrating a very high level of interest on the topic of sleep and Down’s syndrome. It is presented here in blog format, edited for clarity. To watch the original presentation with visual slides, you can watch here in full, or via the video segments that are linked with each blog.

You can watch this section of the Webinar here on YouTube.

Introduction and Welcome

Dr Corcoran: I would like to invite Dr. Cathy Hill up on the stage. Welcome, Kathy. It is so good to have you here today.

Professor Cathy Hill: I like the idea of the stage. I have been talking to myself in my office! It is actually lovely to see some faces. Thank you to those of you who are brave enough to put your cameras on. It makes it so much more real than sitting and talking to a screen. It is fantastic that so many people have joined. I know when Lizzie proposed this, I had no idea we were going to have so many people interested, and that is great. I think that speaks volumes about how important sleep is to children and to families. Certainly, that is my lived experience.

Dr Liz Corcoran: To introduce you, Dr. Hill is down in Southampton. You are an associate professor of child health within the university medical school there. Obviously, your focus is on sleep, and you definitely have a heart for our community. You have done a few research projects on children with Down syndrome to work on understanding sleep better, and you would love to do more, and we would love to see that happen. So, I will get out of your way and let you begin telling us a little bit about sleep in Down syndrome.

Professor Cathy Hill: Thank you to the kind parents who shared this beautiful photograph of these two gorgeous twin boys. What a lovely image. I have stolen it and put it on the header slide because I thought it was such a great image. Thank you, Liz, for that lovely introduction.

Presentation scope: As Liz said, I have been really interested in sleep generally in children with Down syndrome now for about ten years. What I want to do today is to talk about sleep in general. When Liz said, "Let's talk about sleep," I thought, "Gosh, which bit of the ten hours of talks am I going to give on this?" because there is so much we could talk about. It is such an interesting area. So, I hope I hit the spot today and focus on things that are relevant to you.

Clinical experience: My interest is very much inspired by my clinical work. As well as doing research, I am a pediatrician and I run a sleep clinic where we have around 500 referrals a year; amongst the children we see are quite a few children with Down syndrome with a variety of different sleep problems.

The Basics of Sleep Physiology

Understanding physiology: First of all, I think sleep is quite poorly understood.

I think we cannot really understand why children have sleep problems and what those problems are about unless we have some fundamental understanding about sleep physiology – basics as to what sleep is and what is happening.

The importance of sleep: It may not surprise you, but even in medical school, we teach very little about sleep. I am sure this was Liz's experience and it was certainly my experience. Yet when you think about that in the context of children: children spend half of their breathing hours asleep. There has to be something jolly important happening in the body and in the brain during that time for us to spend all that time in this level of altered consciousness.

States of the brain: I am going to show you a few images to cue you in a little bit about some key facts about sleep. I think most of you will probably appreciate that sleep is not one thing. It is fundamentally a state of the brain. It dictates your whole body physiology.

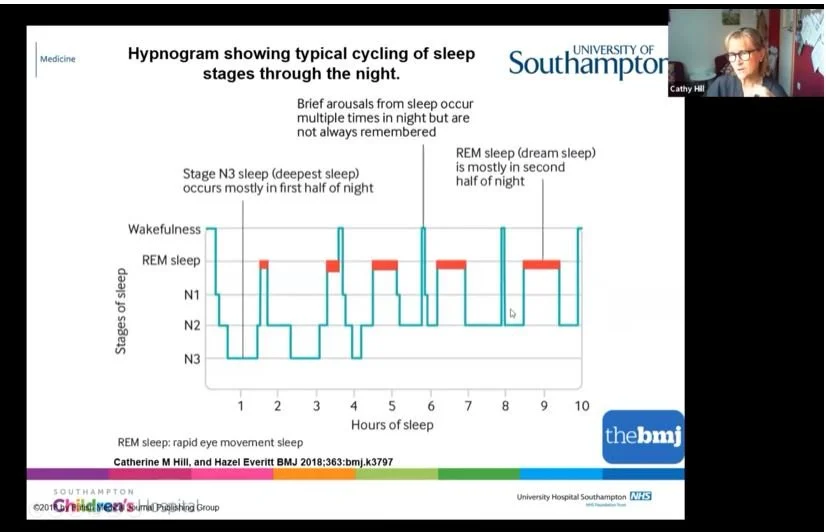

Depending on what state of sleep you are in, different things are happening throughout your body with your hormones, your heart, your breathing, and your temperature control. It affects just about every aspect of your bodily functions. As I said, sleep is not one thing; it is a whole series of different brain states. This is a little diagram illustrating what that looks like.

The sleep journey: During the night, your brain takes a journey through the landscape of sleep. We start off in wakefulness at the top and progress quite rapidly. For children or adults who fall asleep easily, off we go into the journey of sleep.

Deep sleep: The first bit of sleep we hit quite quickly is our deep sleep, and it is called deep sleep because it is actually hardest to wake up from. Many parents say to me, "It might be a real struggle to get my child to sleep, but once they are asleep, we know we have that precious little hour when they are going to be quiet." That is because they are sitting there in their deep sleep. You can see that deep sleep is mostly in the first few hours of the night.

Dream sleep: Very often parents will say they are quite settled at the beginning of the night, but then it all changes as the night goes on. The reason it changes is that as you progress through the night – you can see these red lines here – this is dream sleep.

You have more and more dream sleep as the night goes on.

Fragility of sleep: Dream sleep, contrary to what people often think, is actually very fragile. It is a sleep you can easily wake up from, and that is why we remember our dreams sometimes if we wake up out of them. As you go through the night, your sleep gets lighter; so, stage three sleep is deeper, and as we go, it becomes lighter sleep.

Normal night wakings: Basically, as the child goes through a night's sleep, they are more and more likely to wake up. In fact, we have natural wake-ups about once an hour after our deep sleep is done at the beginning of the night. A very important message is that waking up at night is normal. We all do it multiple times. It is usually quite brief and we do not always remember it. A lot of us might remember waking up and checking the clock – great, it is 3 o'clock – and we might get up and go to the loo. Children do this as well. A lot of the problems that children have with night waking relate to these natural night wakings that then follow on to a behaviour, and we are going to come back to that in a minute.

Muscle control in sleep: Another little fact I want you to grasp at this point is that everything in your body is different during the different sleep stages. That includes our muscle control. An important thing to be aware of is that in dream sleep, we switch our muscles off; we effectively become paralyzed from the neck down. That stops us running around the room and acting our dreams out.

Floppy sleep: This becomes important when we talk later about sleep apnea because it means that all of our muscles, including the muscles at the back of our throat, become a little bit floppy. So, hold onto that little fact as we go through: dream sleep equals floppy sleep because we are paralyzed.

How Much Sleep is Needed?

I think the question I am probably asked most often by parents is, "How much sleep should my child have?" The answer is: as much sleep as they need. It is a very difficult one to answer because every child is different.

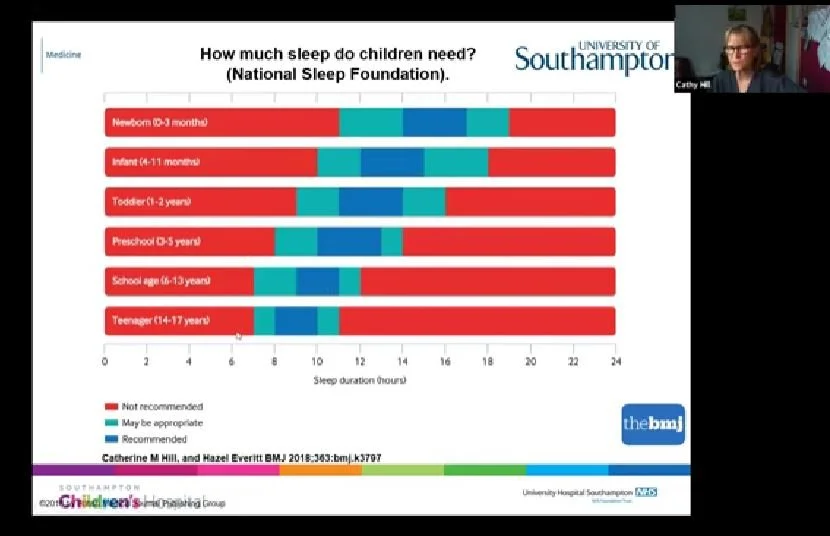

Sleep guidelines: This is an interesting graphic that shows ideal amounts of sleep (dark blue blobs), what might be okay (turquoise blobs), and the bit that probably is not okay (red blobs). As you can see, it changes through life. When children are born, they need a lot of sleep – we all know that. As you progress through life into the teenage years, you need less and less sleep.

Variation by age: Pretty typical for a teenager might be about nine hours, and for a school-aged child it might be around ten hours, but as you can see, there is huge variation around this.

These figures were not derived from somebody guessing and plucking numbers out of the air. This was from reviewing 700 research papers and looking at the associations between how much sleep children had and what happened to them – their physical health, their mental health, and their ability to think and stay on task. So it came from science; it is not absolute, but it is a kind of guide.

Measuring enough sleep: There is a huge amount of variation. The bottom line is, if your child can ping out of bed in the morning feeling reasonably refreshed and does not show signs of tiredness in the day, chances are they are getting enough sleep. It is quite a tricky one to measure. Of course, what we know with children is that, unlike adults, they do not just look sleepy. Quite often they become dysregulated, their behaviour goes off, and they are more hyperactive or more challenging; that can be a sign of sleepiness in children. It can be very confusing and difficult to spot sleepiness in children.

Factors That Influence Falling Asleep

What makes us go to sleep? We all imagine it is this magic process where there is like a switch in your brain and you just go to sleep. It feels like it should be natural – something we can just do without really thinking about it. Surprisingly, it then becomes very frustrating if we cannot or if our children cannot.

Brain readiness and age-appropriate bedtimes: I want you to think about some of the key things that have to be right and lined up in order to go to sleep. First of all, your brain has to be ready for sleep. What does that mean? That means you have to be tired. You might think, "This isn't much of a lecture, that's pretty obvious, isn't it?" However, it is not always obvious to people. I have come across many parents, particularly when children have learning disabilities or physical challenges, who might put their child to bed a wee bit too early and haven't thought, "Well, actually, my child is now 15." Your typical 15-year-old goes to bed much later; they are not going to be going to sleep at 7:00 in the evening anymore like a younger child might.

We have to be tired, which means we have to have been awake for long enough to have that brain urge and brain readiness for sleep.

The body clock: The other thing that's perhaps a little less obvious is our body clock – our endogenous body clock – which sits deep in our brain and tells us approximately when we want to go to sleep. That peaks at about 3:00 in the morning; so, if you are trying to do an all-nighter or a night shift, that is the time when it is hardest to stay awake. If your body clock is completely out, which it can be in some sleep disorders, it is very hard to go to sleep even if you are tired. That is what happens when we get jet lag.

Relaxation and calm: As well as your brain being ready, we also have to be relaxed and calm. We all know this from lived experience. If you have any worries, if you go to bed stewing about something, or if you are stressed because you have to get up early to catch a train, it is much harder to fall asleep. For children, that can be very relevant if they are hyped up, anxious, phobic about school, or fearful; it is much harder for them to settle to sleep.

Physical and sensory needs: The physical environment needs to be right, and we are going to talk a bit about what that involves. Of course, you have to be free from pain. We see a lot of children who have particular sensory needs. Have those sensory needs been met in the run-up to bedtime over the day, and are their sensory needs being met in bed?

Temperature and hunger: You have to be the right temperature – not too hot and not too cold – and it helps if you are not hungry. It equally helps if you are not full of food because a big meal or a big tube feed just before you go to bed is going to make it much harder. Your body naturally slows down its gut digestion during sleep, so it helps not to have a full tummy when you go to bed.

The choice to go to bed: This is the one that people forget about: we all make a choice to go to bed, don't we? After about four days of trying to stay awake, you lose that choice and it becomes involuntary. But we all make a conscious choice that it is now time for me to go to bed.

So, there is a huge cognitive and behavioural aspect about going to sleep. That is very much true for children as well. That is where some of the things you can do can be very helpful to help the child be in the right cognitive state of readiness for going to bed.

Common Sleep Challenges in Down Syndrome

Through the research over the years, what have parents told researchers about children with Down syndrome and their sleep? There is a famous, well-known sleep questionnaire that is often used, and I have pulled all the data across hundreds of children.

Bedtime resistance: These children are more likely to be resistant at bedtime than their non-Down syndrome peers. Resistance is very much about behaviour – not being happy to go to bed, not wanting to go to bed, or putting up a fight about it. They are more likely to be anxious about going to bed.

Waking and restlessness: They are more likely to wake at night and more likely to have problems with breathing at night. They are more likely to be restless. I hear this so much. "My child is very restless, tossing and turning, throwing the sheets off, upside down, left, back to front, all over the bed, moving around." Some of that is about rocking at night.

Daytime sleepiness: They are more likely to be sleepy in the day, which is a real red flag because, as I mentioned, children tend to go a little hyper before they actually become sleepy. Sleepy children really do tend to be properly sleep-deprived children.

Objective measurements: There have been studies that use what I call objective measures. They use equipment and monitoring to look at what's different about sleep in children with Down syndrome. Here is what those research studies have shown. First of all, thinking about actigraphy: this is the fancy medical word for a kind of Fitbit you or the child wears at night that measures movement and downloads it into software so we can guess when the child is sleeping and when they are awake.

Poorer quality sleep: What we see is shorter sleep and poorer quality sleep, with a lot more interruptions and night wakings. When we put children into sleep laboratories, where we look at brain waves, sleep states, and sleep stages, the data isn't very consistent, to be honest. Some studies say one thing and some say the opposite.

But there is a common thread running through this: if there is one feature that is seen more consistently, it is less dream sleep. I'll come back to that later. Some of you might be asking why that is.

Importance of Sleep for Development and Health

Are we bothered? Every parent who cannot get a good night's sleep is bothered and does not need to be told this is important, because you know yourself what it feels like not to sleep.

Research in development: However, there is some fabulous research now that tells us why sleep is important for child development and health. I could spend hours talking about it, but I'll give you some headlines.

Experimental sleep restriction: This is about typically developing children. There have been some very smart studies called experimental studies. This is when you take a group of children and expose them to sleep restriction. They have a few nights when they do not have enough sleep and some nights when they have normal sleep, and you spot the difference. You are comparing the same child between good sleep and bad sleep.

Impact on attention: Those studies show that children very rapidly – even over three days, and I am not talking about crazy all-nighters, but maybe 45 minutes less sleep a night – show a difference in how well they can stay on task and pay attention, how well they can control their behaviour and emotions, and how restless and impulsive they are in the day. That's from a really small amount of sleep deprivation. Think about that over a long period of time and what it does to children and their ability to learn in class if they are restless and cannot pay attention.

Physical health risks: If you follow children up over time, we know a whole load of stuff can happen. We know you are much more likely to be overweight and obese if you have short sleep, even in early childhood. We did some studies here in Southampton looking at children when they were three and measuring body fat mass; children who weren't sleeping enough at three were much more likely to have a lot more fat in their body at age six.

Brain development: Stunning data in long-term studies has shown that not having enough sleep in the early years can even affect how your grey matter, your clever brain, develops. That's very new and exciting data because if there were one reason why children should sleep, it's for their brain development.

We have to ask ourselves why little babies sleep so much. What's going on that means babies need to sleep so much while we need to sleep less and less as we get older? It probably is related to brain development.

Research in Down syndrome: But what about children with Down syndrome? As Liz said, the research often follows later because it is harder to get funding for this kind of work. From my own experience, we have had absolutely fantastic support from parents; that has never been an issue. Once you get the funding and a project up and going, we've had some really fabulous support from parents in the past, volunteering their children to take part in research, which is great.

Language and behaviour: What do we know? We know there's an association in little children – this was some fabulous work from Arizona – between short sleep and both daytime behaviours and language development. Compared to the thousands of children studied without Down syndrome, the numbers are still low regarding how it impacts daytime well-being and behaviour.

Cognitive reserve: But I've always argued that children with Down syndrome have less "cognitive reserve" to call on. If you already start with some learning challenges and then throw another challenge in like not getting enough sleep, you haven't got as much reserve there. If we were able to do the same amount of research as has been done for typically developing children, I think those effects might even be greater.

Upcoming: Part three focuses on how children with Down syndrome experience sleep, and what research specific to Down syndrome tells us about this.